Evolution of the Pilot Boat: From Wooden Schooners to High-Tech Launches

Arguably there are no two names more closely related to Pilot Boat design and construction in the United States than Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding and Ray Hunt Designs. Together the dynamic duo has designed and built more than 80 vessels – not to mention a vibrant refurbish and repair operation – design and building for pilot organizations around the country. In a recent episode of Maritime Matters: The MarineLink Podcast, a trio of executives: Peter Duclos, President, Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding; Winn Willard, President and Robert Provencal, Designer, Ray Hunt Designs, discuss the evolution and future of boat design for this demanding operation.

For centuries, pilot boats have been the unsung heroes of maritime commerce. These specialized vessels meet deep-sea ships at sea, transferring local pilots who guide vessels safely through harbors, rivers, and channels. The job demands vessels that are fast, seaworthy, rugged, and above all, safe. In the U.S., few companies have had a greater influence on the evolution of the modern pilot boat than Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding and Ray Hunt Designs.

From Wood to Steel: A Post-War Revolution

Gladding-Hearn’s pilot boat legacy traces back to 1957, when the Delaware pilots approached the Somerset, Mass., yard with a unique request. “They came to us and said, ‘Hey, that looks very close to one of our wooden pilot boats. Can you build a steel one?’” recalls Duclos. “At the time, all pilot boats were wooden, largely because of concerns about sparks near tankers or gasoline ships. But after World War II, the advent of rubber fenders made steel feasible.”

“So Mr. Gladding and my father went down and looked at it. And they came up with a 10 knot, a single screw pilot launch. Even today, those are, in my estimation, the best sea boats I've ever been on for a 48-foot boat. I'd take one literally anywhere. They're like a schooner without a mast. They're very deep keel, lots of concrete in the bilge, and they’re so comfortable.”

For two decades, those steel launches served reliably – but they were only capable of going 10 knots, and the pilots came calling again, this time with the need for more speed.

“We built quite a few of those over the years, and then fast-forward to the mid-1970s, and again the Delaware pilots came to us and said, ‘Hey, we love your boats, but we want to go faster, and you really need to work with these guys at C. Raymond Hunt. They make great offshore boats, great high-speed boats.’"

“That’s how we got into pilot boats. We collaborated with Gladding-Hearn in 1978, building the first Hunt-designed pilot boat for the Delaware pilots. It made 20 knots—a real leap forward at the time.”

“That’s how we got into pilot boats. We collaborated with Gladding-Hearn in 1978, building the first Hunt-designed pilot boat for the Delaware pilots. It made 20 knots—a real leap forward at the time.”

-Winn Willard, President, Ray Hunt Designs

Image courtesy Ray Hunt Designs

Enter the Hunt Deep-V

By the mid-1970s, the Delaware pilots wanted faster launches. They encouraged Gladding-Hearn to team with C. Raymond Hunt Associates, already known for pioneering offshore high-speed hulls. “That’s how we got into pilot boats,” says Willard. “We collaborated with Gladding-Hearn in 1978, building the first Hunt-designed pilot boat for the Delaware pilots. It made 20 knots—a real leap forward at the time.”

The breakthrough was the Hunt Deep-V hull, patented in the early 1960s. Unlike flat-bottomed boats that pounded heavily in rough water, the Deep-V offered a steep deadrise and straight buttocks lines, enabling planing performance while maintaining comfort offshore. “Ray Hunt showed the world you didn’t have to have a flat bottom to go fast,” said Willard. “The Deep-V was both fast and capable in rough water, exactly what pilot operations demanded.”

Over the past 45 years, more than 80 Hunt-designed pilot boats have been delivered in partnership with Gladding-Hearn, evolving from steel to aluminum, and from 20-knot launches to modern boats capable of 30 knots or more. Today, pilot boats make up roughly a quarter of Ray Hunt’s design work.

Watch the Ray Hunt Designs Alaska 75-ft. pilot boat in action. (Video courtesy Ray Hunt Design)

Tailored to Local Waters

One of the defining features of pilot boat design is its customization to local geography. “Every port is different,” notes Duclos. “Some pilots run 30 miles offshore, others just a few miles. Some boats are simple day launches, others are liveaboard vessels.”

The design process begins with a close study of local operating conditions: run length, sea state, climate and boarding practices.

“Ultimately, they all do the same thing: safely put a pilot on a ship,” says Duclos. “That requires excellent fendering, visibility, handrails, and deck layout. Comfort is also critical. Pilots go out when nobody else wants to. They need to feel safe, not arrive injured or exhausted.”

For Provencal, who began his career at Gladding-Hearn before joining Ray Hunt nearly 40 years ago, the collaboration is second nature. “Peter and I can anticipate each other’s conversations,” he says. “Every pilot group thinks they operate in the worst conditions in the world. And in a way, they’re all right.” Pilot boat construction at Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding.

Pilot boat construction at Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding.

Photos courtesy Gladding-Hearn ShipbuildingFrom Offshore Stations to Fast Launches

A major shift in pilotage came with the transition from offshore station vessels to high-speed shore-based launches.

“In Boston, as late as 1967, the pilots still used wooden schooners offshore,” recalls Willard. “They’d row out in 18-foot skiffs to board ships, which had to stop completely. High-speed launches eliminated the need for offshore stations, saving pilots and shippers enormous costs. Today, only a three places in the U.S.: New York, San Francisco, Houston, still use station boats.”

Modern launches now routinely board ships traveling at up to 15 knots, a testament to both vessel design and pilot skill. “Comfort, in terms of pilots, is a very high threshold compared to the typical person off the street. They go out when nobody else will go out. But at the end of the day, while they all vary in terms of their arrangement, they all do the same thing: they have to come alongside a ship, put a pilot on safely, predictably, in all kinds of weather, and get away from the ship.”

“Comfort, in terms of pilots, is a very high threshold compared to the typical person off the street. They go out when nobody else will go out. But at the end of the day, while they all vary in terms of their arrangement, they all do the same thing: they have to come alongside a ship, put a pilot on safely, predictably, in all kinds of weather, and get away from the ship.”

-Peter Duclos, President, Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding

L to R: Peter Duclos, his sister Carol Hegarty (CFO), and brother John Duclos (Co-President and Director of Operations) carry on the family business of boatbuilding in Massachusetts.

Image courtesy Gladding-Hearn Shi8pbuildingTechnology on the Forefront

While pilot associations tend to be conservative, new technologies are steadily reshaping pilot boat performance. Duclos points to the Volvo Penta IPS pod system as a significant development: “IPS boats burn 30% less fuel. That’s real, measurable efficiency. Some groups are cautious, concerned about ice, debris, or service support, but for those adopting it, the benefits are clear. I'm not sure why people aren't really jumping up and down, and saying, ‘I've got to have one.’"

Other advances include ride control systems — interceptors and gyro stabilizers — that improve comfort and efficiency. “With ride control, you can adjust the boat’s attitude to speed,” says Willard. “Pair that with IPS pods, and you have a very efficient package.”

Local water conditions and length of run have been the biggest driver for pilot boat technology evolution.

“Back in the day with the smallest single-screw steel boats, you had a compass, a couple of pilot seats, a rubber fender around the boat … and that was it; that was a pilot boat,” said Duclos. Today though, the complexity has elevated as onboard noise and vibration control play a large part in keeping pilots physically and mentally ready for their job. “Comfort, in terms of pilots, is a very high threshold compared to the typical person off the street. They go out when nobody else will go out. But at the end of the day, while they all vary in terms of their arrangement, they all do the same thing: they have to come alongside a ship, put a pilot on safely, predictably, in all kinds of weather, and get away from the ship,” said Duclos.

To that end modern pilot boats have high-end [shock mitigating] seats to deal with the higher speeds; a really good fendering system; good visibility from all angles so the operator has a view of the pilot and crew at all times; handrails must be well-positioned.

Hybrid-electric propulsion remains under study, though Duclos is cautious: “Hybrid doesn’t really fit pilot operations. Boats are either on or off, without much loitering. Batteries might work for short runs, like Los Angeles pilots, but not everywhere.”

If technology has advanced, one thing has not changed: the need for reliability and ease of maintenance.

“Gladding-Hearn boats are designed with maintenance in mind,” says Willard. “Systems are accessible. Wiring isn’t buried, plumbing comes apart easily, and pilots appreciate that.”

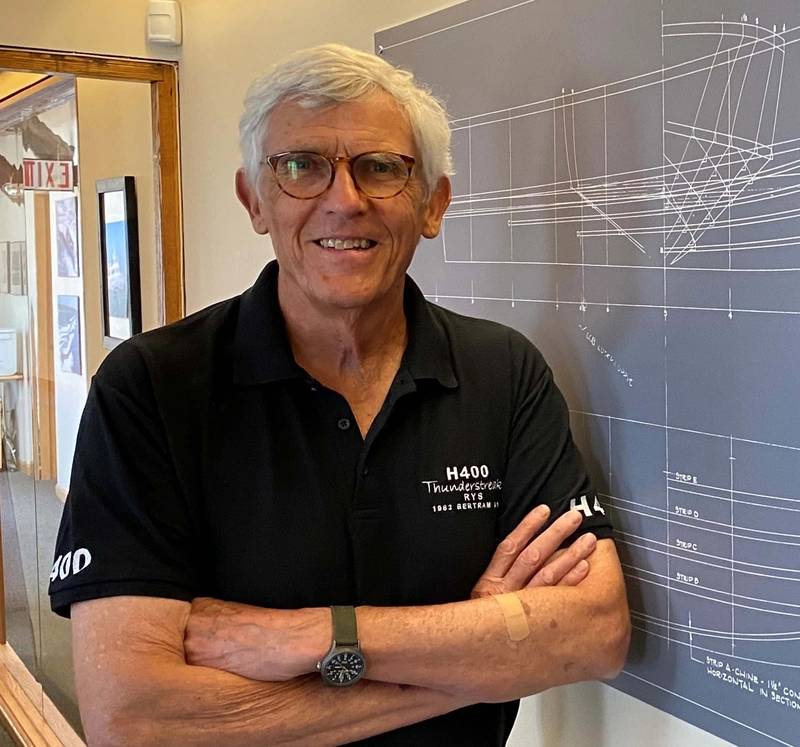

Feedback from pilots drives continuous refinement. “If they say a generator needs to be moved six inches for service access, we listen,” Duclos explains. “Good design is what makes a boat reliable. If the design isn’t right, it doesn’t matter how skilled the builders are.” “Peter and I can anticipate each other’s conversations,” he says. “Every pilot group thinks they operate in the worst conditions in the world. And in a way, they’re all right.”

“Peter and I can anticipate each other’s conversations,” he says. “Every pilot group thinks they operate in the worst conditions in the world. And in a way, they’re all right.”

-Robert Provencal, Designer, Ray Hunt Designs, who started his career at Gladding-Hearn before joining Ray Hunt Designs nearly 40 years ago.

Image courtesy Ray Hunt DesignsThe Market

Despite regulatory uncertainties, such as right whale protection rules that may impact vessel size and speed, demand for new pilot boats remains steady.

“We’ve got four under contract now,” says Duclos. “But there’s reluctance in some ports to commit until regulations are clear. At the same time, boats wear out. They run 3,500 hours a year. Eventually, they must be replaced.”

Gladding-Hearn also maintains a robust refit program. “At 15 years, the boats still have good bones,” Duclos says. “We replace machinery, electronics, windows, seats — essentially making them like new for half the cost and time of a new build. It’s a smart option for many organizations.”

For Duclos, Willard, and Provencal, the evolution of the pilot boat is both a technical challenge and a deeply personal mission.

“These little boats have benefitted the entire maritime industry,” says Willard. “They’ve made pilotage faster, safer, and more efficient. And they continue to evolve with technology and customer needs.”

Watch the full Maritime Matters: The MarineLink Podcast as Peter Duclos, President, Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding; Winn Willard, President and Robert Provencal, Designer, Ray Hunt Designs discuss the evolution of Pilot Boat design and construction premised on a portfolio of more than 80 boats built over the span 40+ years.